A media plan is a system in which multiple lines compete for the same budget and serve the same final objective. For this reason, a single underperforming line does not automatically put the entire plan at risk.

One of the most commonly overlooked aspects of media plan analysis is the relationship between lines.

In many cases, a plan remains healthy precisely because other lines compensate. A strong media plan is not one in which every line looks perfect, but one that has enough flexibility to absorb tension without compromising the final result.

A line becomes truly problematic not when it is below target, but when there is no longer any room for compensation elsewhere in the plan.

A media plan should not be read through absolute differences, but through rhythm.

To do this properly, a clear comparison between planned and achieved is essential. Whether automated or manually done(not recommended), this comparison is the foundation of any meaningful analysis.

Every solid review should start with two simple questions:

These questions move the discussion away from quick verdicts and into feasibility. The issue is no longer whether performance is above or below plan, but whether what the remaining numbers demand is still realistic.

A plan can look comfortable at a given moment and still become impossible to complete. Likewise, it can appear tense early on and stabilize later. Without pacing, these nuances remain invisible.

Regardless of channel or objective, every media plan line can be assessed through two essential dimensions.

Budget pacing shows whether a line is ahead or behind the plan. A daily remaining budget that differs significantly from the original estimate signals tension, regardless of whether that tension appears positive or negative.

Budget deviations are not inherently good or bad. They only become meaningful when viewed in the context of the remaining time and the plan’s ability to absorb that variation.

More important than what has been achieved so far is what needs to be achieved from now on. Analysis should not stop at whether a line is performing well or poorly, but focus on the realism of the pace required for the remaining period.

When the remaining numbers require an unrealistic jump compared to current performance, the problem is not one of volume, but of feasibility.

The opposite case is just as relevant. When performance is significantly better than estimated, the result may be positive, but the gap still signals something worth examining. It can indicate an overly optimistic estimate or a meaningful difference between planning assumptions and actual implementation. That difference may relate to audience selection, placements, or bidding strategy, without any of these being inherently “right” or “wrong”.

Both extreme underperformance and extreme overperformance are signals for analysis, not final judgments.

The overall view of a media plan can look acceptable while structural issues remain hidden underneath.

Real tension almost always appears at line level. Some lines pull the plan forward, others hold it back. An analysis focused only on totals masks these dynamics and creates a false sense of control.

A healthy plan is not one where every line performs perfectly, but one where imbalances are visible, understood, and manageable over time.

Analyzing a media plan is not about reacting quickly to deviations, but about understanding pace and feasibility over time.

A good plan is not one that looks good in a report at a specific moment, but one that can be carried through to the end without demanding the impossible. The role of analysis is to surface real tension early, before it turns into a structural problem, not to chase perfection at line level.

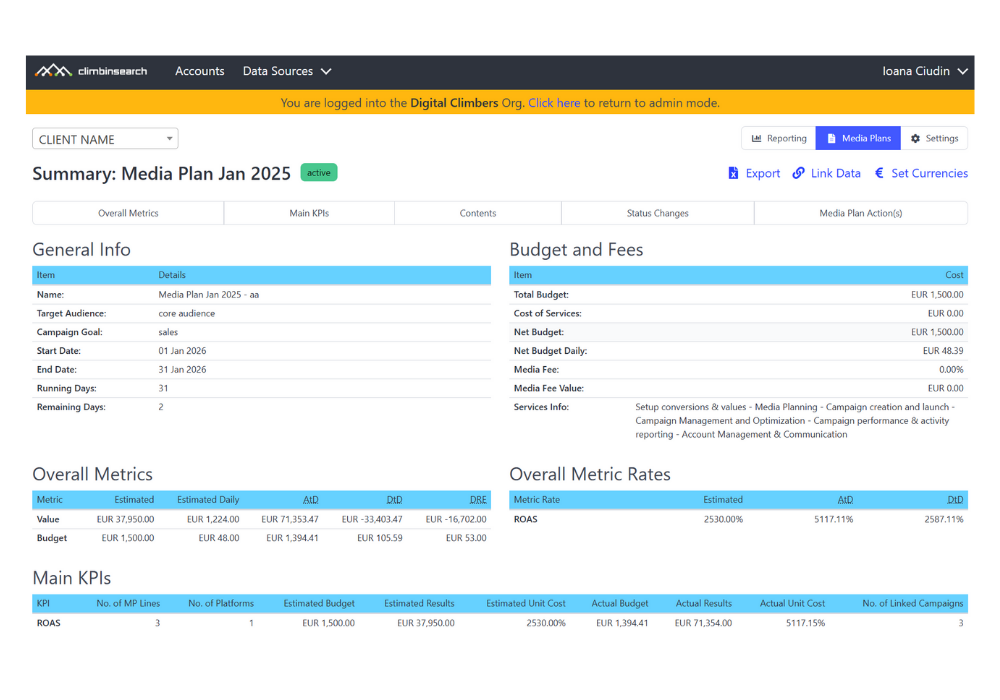

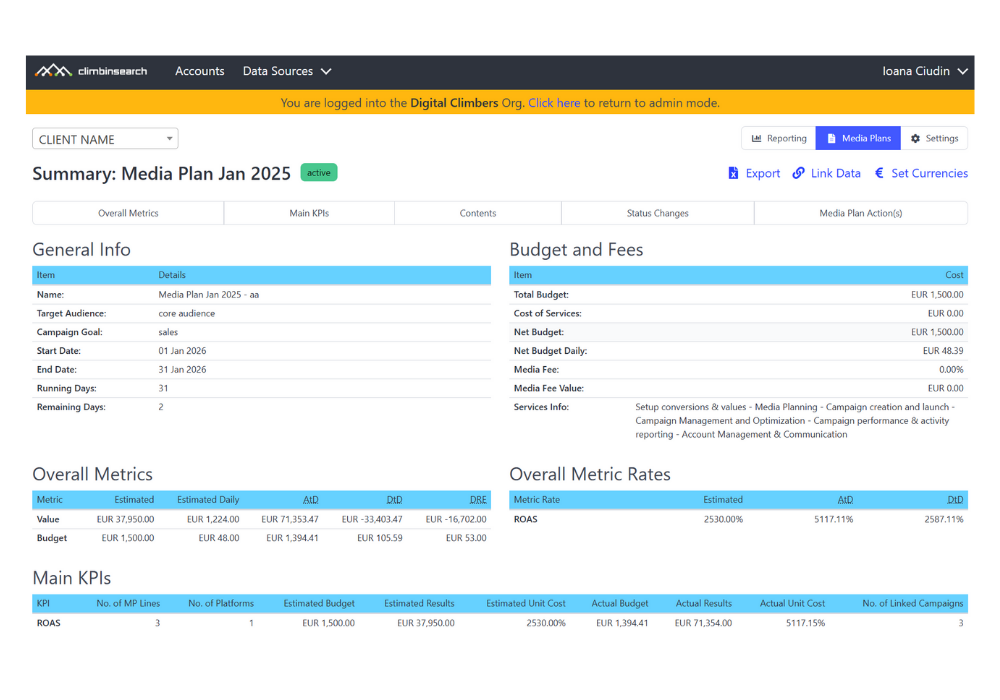

This way of thinking is also reflected in how the Media Planning module in ClimbinSearch is built: around a constant comparison between planned and achieved, pacing visibility, and the ability to understand how individual lines interact inside a single system, not just how they perform in isolation.